How long will the Russian economy be able to sustain the war in Ukraine? By most traditional measures, the economy is in surprisingly good shape. However, these metrics may be deceitful when analyzing the true nature of Russia’s wartime economy and the challenges that Russian President Vladimir Putin and his successors will face going forward.

Of course, Russian officials and propagandists alike love to boast that Russia’s GDP growth is stronger than that of many European countries. What they leave out is the fact that the contours of the Russian economy are increasingly dominated by highly unusual trade relationships with the rest of the world following the imposition of unprecedented economic sanctions, restricted capital flows, and strong state involvement. Russia is undergoing a major restructuring of its economy and experiencing significant changes in wealth and income distribution patterns among population groups.

To the great relief of the Kremlin, the shock of the full-scale invasion in 2022 and the subsequent severing of trade and financial ties with the West is now largely in the rearview mirror. The Russian economy has adapted, and key industries have found ways to get the goods and components they need from alternative suppliers or via more circuitous trade routes. Logistical disruptions did not lead to lasting stoppages in production, and Russia’s foreign currency earnings are now comparable to prewar years. A large part of the economy has been restructured to meet the needs of the military. Production of military goods has expanded, including both relatively simple items like artillery ammunition and more complex technology such as Il-76 transport planes and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

At the same time, it is potentially misleading to rely mainly on traditional measures of macroeconomic success—such as inflation, interest rates, and GDP growth—as indicators of what is going on in Russia today.

In market economies, the authorities influence economic actors by sending them signals: both rhetorical and through actions (like raising interest rates). Officials are judged on their decisionmaking by businesses and the broader population. Using the signals from the authorities, outside observers can assess the economic situation in any given country.

None of that is fully applicable to modern Russia. Of course, Russia does not have a planned economy like the Soviet Union, nor even the so-called goulash socialism of some Central European states from the 1950s through the 1980s. At the same time, today it would be wrong to speak of Russia as having a free-market economy. The system in place is dirigisme: active state involvement in all economic processes.

Russia’s Prewar Strategy

When the Kremlin launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it was counting on a rapid victory. It expected to quickly install a pro-Russian government in Kyiv and present the world with a fait accompli. If that had happened, the thinking was that the West would have found it hard to sustain broad-based sanctions that would be painful for the health of the global economy. The first phase of the war that began in 2014 had demonstrated that there were plenty of advocates of sustaining business as usual with the Kremlin.

Russian officialdom also anticipated that the West would be unwilling to take decisive action in the area in which it depended on Russia the most: energy. For Russia, any such confrontation would surely have financial consequences, but the availability of ample reserves has long been treated as a key insurance policy for the Putin regime. In 2022 there was also confidence in Moscow that any energy price spike resulting from a full-scale invasion of Ukraine would compensate for any near-term fall in sales to the West. It was believed that Europe would be unable to line up alternative suppliers for its energy needs quickly, which would convince European capitals of the strength of Russia’s position.

In other words, a belief in Kyiv’s rapid capitulation was at the heart of Putin’s military and economic strategy. But the Russian military failed to pull off a blitzkrieg. While Russian forces managed to occupy about 20 percent of Ukrainian territory, attacks on major cities were unsuccessful. Russian forces eventually retreated from the southern Ukrainian city of Kherson, the only Ukrainian regional capital seized in 2022.

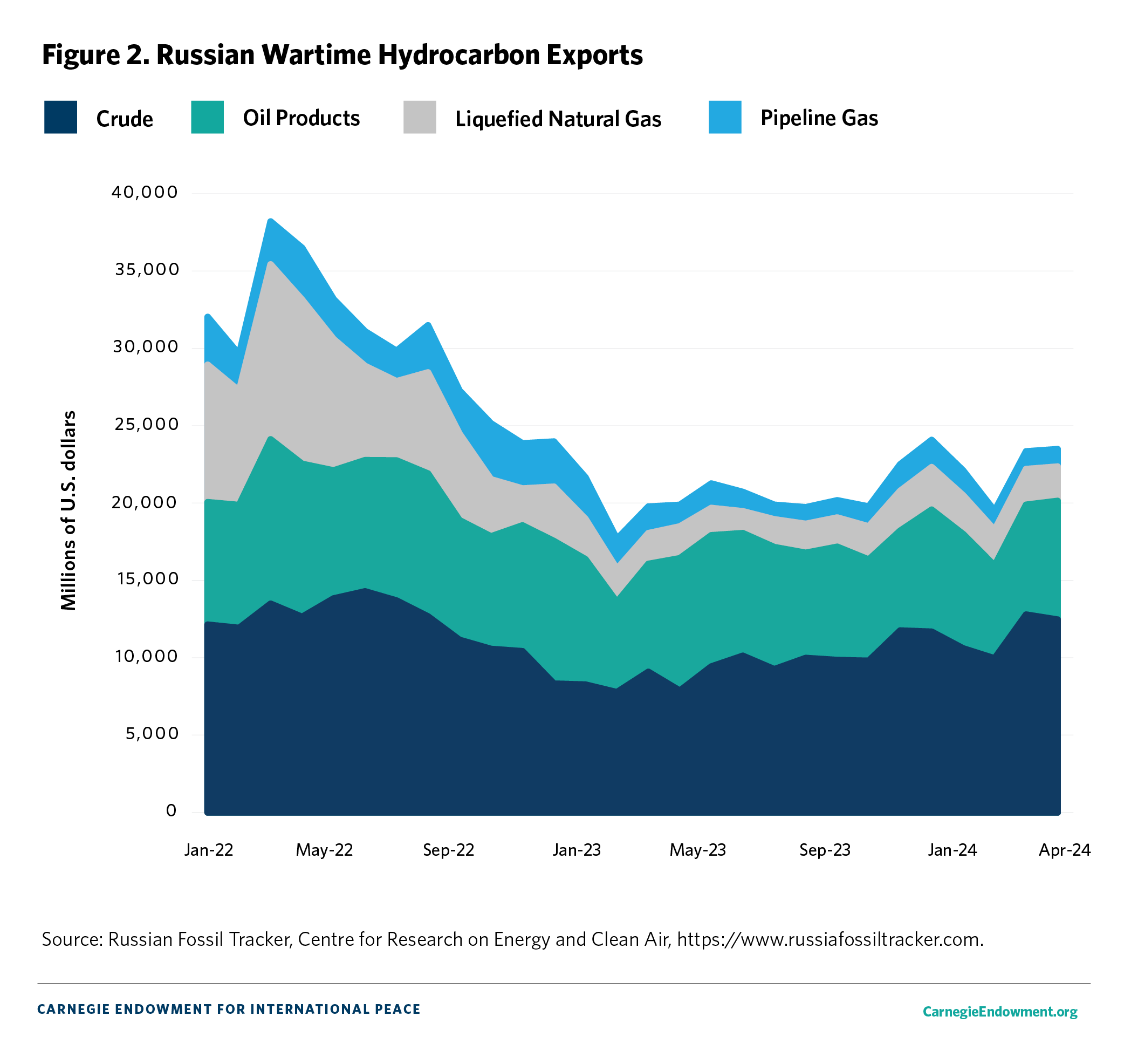

At first, the energy war was more successful. Russia’s profits from energy exports rose and Europe suffered a significant economic shock in 2022. But the gas market began to stabilize the following year, and the European economy adapted to high prices (albeit at considerable cost to energy-intensive manufacturers). As a result, Russia’s profits from gas exports declined.

When it comes to oil, the energy war is—for the moment—a draw. Russia continues to export oil and oil products without any restrictions in terms of quantity, and world oil prices are higher than before the war. Russia has defied G7 attempts to impose a price cap but has incurred higher transaction costs, which have reduced its oil export profits to about the same level as prior to the full-scale invasion (see figures 1 and 2).

Putin’s Economic Goals

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s objectives align nicely with those of every other dictator: to retain power and to realize his ambitions. Both of these goals require resources. Of course, a dictator’s ambitions can vary. Some seek to enrich themselves or their clan. Some want to carve out a place in history as the leader of a thriving country, a country that has acquired new territory, or a country that has cowed its neighbors.

With time, Putin’s ambitions have become more militaristic and more expansionist. But war is an expensive hobby. What is now a war of attrition in Ukraine has forced the Kremlin to change its military and economic approach. Accordingly, the Kremlin’s economic policy now has a double focus. Firstly, it needs to provide enough resources—material and human—to sustain the military. Secondly, the broader population needs to retain a sense of normalcy, which means ensuring there are no dramatic changes to standards of living. Without this stability, threats to the regime could emerge.

Ahead of a pro forma presidential election in March, Putin ramped up elements of repression, making the current regime more draconian than at any other point in the country’s post-Stalin history. Even though the election period is now over, it appears that repression will intensify even further. The agenda of the Russian government will be implemented via the stick, rather than with carrots. Nevertheless, the well-being of the population will remain important. In his preelection speeches, Putin made endless promises that will cost trillions of rubles to implement.

Two years after the start of the full-scale war, the base case scenario is now a long conflict. The Russian side does not believe in the possibility of losing, nor is it naïve enough to anticipate the lifting of sanctions or Russia’s reintegration into the global economy in the near or medium term. Any realistic analysis of the situation should proceed from the assumption that various forms of Western economic coercion against Russia will continue, if not tighten, in coming years.

Remaining Resources

It’s impossible to make projections about the economic decisionmaking of the Russian regime and future trade-offs without knowing what resources they have available. In the run-up to February 2022, Russia had significant foreign currency reserves, extensive stocks of military equipment (some of it up to seventy years old), and a more or less modernized industrial base. The war and sanctions have gradually depleted all of these.

All of the economy’s needs—current consumption, boosting inventories (in case of sanctions being tightened, for example), and acquiring capital goods to maintain or expand future production—can be serviced either through imports or domestic resources. Significantly ramping up domestic production prior to the war was impossible because there was no idle capacity or excess labor resources. After February 2022, however, some resources appeared, particularly as many foreign companies (including those manufacturing cars, household appliances, and electronics) exited the Russian market. The demand for these products, which in no way declined, has had to be met via imports. The Russian defense industry also has a need for imports: reserves of weapons and ammunition are quickly exhausted, and there are not enough resources to significantly boost domestic production.

Imports can be paid for using either foreign currency earnings or foreign currency savings. Before the war, it was often questioned why Russia’s foreign currency reserves were so disproportionally large: what was it saving for? Regardless of what the Kremlin had in mind before February 24, 2022, after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine it became self-evident that the primary purpose of the reserves was to support the war effort and to keep society quiescent.

Russia’s current reserves of foreign currency and gold, which stand at about $580 billion, provide considerable freedom of maneuver. As a result of sanctions, Moscow surely has written off roughly $300 billion that was frozen in Western bank accounts at the start of the fighting, but the ratio of remaining gold and foreign currency reserves to GDP is a good one. (Note: Russian GDP in 2023 was about $2 trillion.) That ratio is roughly equivalent to that of Canada, France, or Mexico, and significantly better than Australia’s.

It is a similar story with other parts of the Russian government’s balance sheet. Russia’s rainy day fund (the National Wealth Fund, or NWF) stood at about 12 trillion rubles ($130 billion) at the start of 2024. Roughly 5 trillion rubles of the NWF is liquid, with the rest invested in long-term bonds, company shares, and infrastructure projects. Those 5 trillion rubles are managed by the Finance Ministry, not the central bank. In addition, about $170 billion worth of foreign currency was held in individual and company accounts in December 2023. The foreign currency debts of the nonfinance sector totaled $220 billion.

The 2023 budget came in with about a $30 billion deficit (about 10 percent of the budget, or 2 percent of GDP). As a result, the NWF shrank by 2.1 trillion rubles (for comparison, it contracted by 300 billion rubles in 2022). In the first year of the full-scale invasion, there were large transfers into the NWF in line with the budgetary rule that mandates moving money to the NWF in periods of high energy prices. There were no such transfers in 2023, and government spending also rose sharply.

What Next?

Russian officials like to describe 2023 as a year of “adaptation.” According to them, the Russian economy was supposed to solve its immediate problems and return to stable growth. This was the context for the 2024 budget.

The plans for 2024 include a 16 percent rise in state spending in ruble terms. Mostly this means military spending (set to jump 70 percent). The spending is needed to replace losses and maintain the army’s stockpiles, since the Armed Forces used up a lot of their weapons—including plenty of Soviet-era armaments—in 2022 and 2023.

Total revenues are predicted by Russian officials to grow 22 percent in 2024. This is a very bold forecast, which relies on several revenue streams rising significantly, including energy exports. The budget assumes, firstly, high oil prices and, secondly, low costs associated with overcoming sanctions on the sale of oil and gas. Even in such an optimistic scenario, there are still plans to take as much as 1 trillion rubles from the NWF.

If spending rises as planned, and revenues stay at the same level as 2023, then according to the author’s calculation the budget deficit will hit about $100 billion (5 percent of GDP). On paper, that is not a lot. The European Union’s relatively conservative rules cap budget deficits at 3 percent of GDP (and that limit has been repeatedly broken by member states). Russia has almost no foreign debt and could easily manage such a deficit. However, as Russia is cut off from foreign capital markets, the deficit will have to be made up with the country’s own resources.

Waging such an expensive war while maintaining a familiar level of consumption and a de facto reduction of production creates a serious imbalance. And it is one that can only be resolved by increasing imports that are paid for by savings and current export earnings. Russia continued to record a stable trade surplus in 2023 (about $30 billion per quarter), which is comparable to the period between 2015 and 2021. However, imports have noticeably risen: they are now worth about $95 billion per quarter, compared to about $78 billion per quarter between 2015 and 2021. There are enough available resources to continue like this for two to three years. By that point Russia’s gold and foreign currency reserves will not yet be depleted, but their levels might start to cause concern at the Finance Ministry and the central bank.

This equation could be changed by external forces beyond Moscow’s control. In one scenario, the current global stock market boom could—as in the past—lead to rising oil prices, and not necessarily because of greater physical demand. Raw materials (or to be more precise, their financial derivatives) have long been seen by stock markets as an asset class, and if they start to look undervalued compared to the rest of the market, investors will put money into raw materials–linked securities. This would drive up commodity prices. In another scenario, if sanctions are tightened (and punishments increased for those helping Russia evade them), then transaction costs for Russia could rise even further, pushing up the cost of imports in turn and causing export revenues to fall.

Economic Outlook

Total victory for either side in this war appears extremely unlikely. It is too early to predict the exact conditions of war termination, but such an unsatisfactory conclusion would likely cause both sides to seek to amass a military arsenal for another attempt to achieve their desired goals—as well as a push to strengthen their defenses. In other words, Russia will be seeking to ramp up military production for years—if not decades—just like between the end of World War II and the détente of the 1970s.

Other forms of expenditure for Russia are also set to rise, for example, benefits for residents of occupied Ukrainian regions and the cost of rebuilding destroyed Ukrainian cities to which Russia has laid claim. Spending on military personnel will likely fall but not by much—and, even if individual soldiers earn less, the total will still be greater than prewar levels.

One constraining factor on the Russian budget is a growing human capital deficit. This is not a new issue. There are fewer and fewer working-age people in Russia: only 1.2 million people were born in 2000, compared with 2.2 million in 1980. The generation born in the 1960s that is now retiring was one of the biggest in demographic history. This will create additional fiscal pressures to finance pensions, and the war has made this problem far more acute. Many young Russians and talented workers fled abroad to escape mobilization. In addition, the number of labor migrants to Russia has dropped as a result of the weakness of the ruble, problems transferring money back home, and the risks of being press-ganged into the Russian army.

As a result, the army, defense enterprises, and other employers are competing for a shrinking pool of working-age—and fighting-age—people. Officials and propagandists like to point out with pride that Russia has almost full employment. But what that actually reflects is an overheated economy caused by a lack of workers.

What Can the Government Do?

One logical response to the situation in which Russia finds itself would be to raise interest rates. That could cool down the economy and slow inflation. However, it also restricts the government’s freedom of maneuver, reducing its ability to take on debt and raising the costs of servicing debt. Raising interest rates usually leads to a strengthening of the currency, capital inflow, and import increases, and it makes more money available for investment.

This is exactly what Russia’s central bank has done. However, the situation in Putin’s Russia is not a textbook one. On the one hand, the economy is more and more isolated, with a rising number of barriers to the free flow of capital both inside and outside the country. On the other, the government has plenty of opportunities to appropriate resources from businesses and individuals and to redistribute those resources as it sees fit. It is making good use of these opportunities.

This means that standard indicators like the budget deficit, interest rates, and the value of the ruble carry far less weight than they would when analyzing a so-called normal economy. Instead, it is worth paying attention to factors such as the total volume of goods and services produced minus military goods produced—in other words, what is available for consumers. Putting industry on a war footing and the necessity of supplying the army mean this number will decline. Of course, Russia can spend its reserves to offset this decline with imports (alongside buying weapons from Iran and North Korea).

It is also worth looking at consumption patterns. Those who have benefited from the war include those in Soviet-era factory towns built around defense plants (where there are lots of new, high-paying jobs). However cynical, the other economic winners have been the families of soldiers, whether alive or dead (since the compensation paid to families of deceased soldiers often exceeds the total expected lifetime earnings of the dead man). Qualified workers who have found employment in construction in occupied Ukraine or Russia’s border regions have also benefited.

Those who have suffered include the Westernized urban middle class, which facilitated the trade between Russia and the West, and those who once worked for foreign companies. There are two major groups that traditionally supported Putin who have lost out: state employees and pensioners. State salaries and pensions are indexed below inflation, and the additional payments that often make up a sizable part of salaries may not be indexed or have even been cut. Savings for old age are being destroyed by inflation.

The Russian state has many ways of redistributing resources among various interest groups and causes, and the government—exploiting a lack of independent parliamentary oversight—has already levied several one-off taxes (mostly on exporters). Another feature of Russian dirigisme has been the state issuing of loans at different rates. While the central bank tries to control inflation by raising the key interest rate to a prohibitively high level, the government is subsidizing loans on favorable terms to certain businesses or making prepayments for defense orders (in other words, issuing a free loan for several months). The state is also giving some employers preferential status on the overheated labor market by shielding their staff from the threat of being mobilized.

Nevertheless, there are limits to Russia’s dirigisme. This is not a planned economy, and the country’s experienced economic managers understand they need to be fast, inventive, and proactive when it comes to circumventing sanctions and rising to other wartime challenges. Decentralization and economic agents’ freedom of choosing the ways and means of achieving their goals (which, admittedly, are broadly set by the government) are seen as one of the reasons the Russian economy coped fairly well with recent pressures, so full nationalization is unlikely. The state will limit itself to distorting traditional economic incentives, creating less-than-optimal economic structures and patterns of production, and cushioning the cost of adjustment for well-connected vested interests. It is unlikely to interfere in the day-to-day management of companies or to create huge state corporations via a new wave of government-mandated mergers.

Will Spending Increase?

In his February 2024 state-of-the-nation address, Putin outlined a series of programs that will require major increases in state spending. Even the few detailed spending announcements—such as student campus construction and a rise in the number of Russian satellites—will cost more than 7 trillion rubles over six years. The minimum wage was also raised by about 10 percent per year through 2030, which has a direct effect on the salaries of state employees and the size of social handouts. Putin also called for a whole series of other programs without a defined budget, but which are likely to be expensive. All this is supposed to be financed by taxing businesses and wealthy Russians. The only problem with this approach is that, traditionally, income taxes were a relatively small part of the consolidated budget (the combined federal and regional budgets), and they flowed, in large part, to regional authorities.

Corporate income tax makes up about 13 percent of the consolidated budget, while personal income tax is about 11 percent. As the current proposal is only to raise income tax for wealthy individuals, it is helpful to look at what the government would get by raising the rate two percentage points for those earning more than 5 million rubles a year: an extra 150 billion rubles (2.5 percent of the total raised via income tax), which would mostly be collected in Moscow and St. Petersburg. In other words, without substantive changes, not much money will be raised. Changes to the tax system that only affect a small minority will not allow the Kremlin to fund all the spending programs it has announced.

Of course, Putin’s track record when it comes to preelection promises suggests that they will remain just that: mere promises. Officials and state-owned companies will be required to make believe that they are working toward fulfilling them, but that is about it.

Certain programs will get their money, however. Consider, for example, the promised 700 billion rubles for the Data Economy program and 100 billion rubles for new satellites. From the Kremlin’s point of view, digitalization will allow it to strengthen control over society and the economy. Meanwhile, there is a lot of demand from the military to shore up Russia’s position in space: the war in Ukraine has shown the importance of high-quality satellite imagery and real-time data feeds on the battlefield.

Can Russia Maintain Its Military Power?

Even without a major rise in state spending, by 2026 the Kremlin may no longer have enough money to simultaneously preserve a façade of normalcy in the country, to wage war in Ukraine, to contend with a more threatening environment along Russia’s western periphery, and to take part in an arms race, especially in the nuclear realm and the development of new high-tech weaponry. Of course, that moment could come sooner—if, for example, the West successfully tightens sanctions, Ukraine seriously damages Russia’s industrial base, or oil prices fall significantly.

The Russian authorities are extremely unlikely to choose to cut military spending in order to maintain previous levels of domestic consumption. The economy is destined to become more and more militarized, even if that results in stagnating or falling real incomes. Still, this is unlikely to cause real problems for the regime. Firstly, standards of living would still remain relatively high: certainly, they have a long way to fall until they reach what they were in the Soviet period, not to mention the destitution of the early 1990s. Secondly, growing repression, the embrace of an avowedly militant and nationalistic state ideology, and attacks on free speech have helped the authorities keep a lid on dissent at home. In an extreme case, they can easily crush any public expressions of opposition. The only real risk is if the salary levels of employees of the security apparatus and military personnel fall below current levels—but the authorities have resources to ensure that this does not happen.

In other words, Russia will be able to maintain military spending for a relatively long time, just like other pariah countries. This is bad news for Ukraine, ordinary Russian citizens, people living in neighboring countries, and the overall global security environment.

There is a scenario whereby the Russia-Ukraine war and the standoff between Russia and the West evolve into a long-term conflict that lasts for decades. In this scenario, Russia might begin to resemble a hermit kingdom like North Korea, whose economy is deeply dependent on China’s generosity and protection. Of course, the Putin regime and its North Korean counterpart operate on the basis of very different ideological foundations and guiding economic principles. In the economic and social realms, the Putin regime has more in common with the attitudes of the leading lights of the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century than with socialism as it evolved under Stalin. At the same time, it is challenging to speak with confidence about how the country’s economic and social structures might develop under a scenario where the current war lasts decades more. It is also challenging to predict what would it take to dismantle the structures on the way back to a Western-style society.

There is a different scenario, of course, which envisions Putin’s rule coming to an end sooner rather than later. If the current regime meets its demise and the Ukraine war ends in a matter of a few years, it is conceivable that a new Russian leadership might want to return to the earlier development path that was abandoned by Putin.

To be sure, the developments of 2022–2024 have created a whole host of problems for whoever succeeds Putin as Russian leader. Demilitarizing the economy will be a demanding process. Some specialized production capacity will be rendered useless. Many people will need to find new jobs or change careers. And all of this will be in addition to the difficulties of reintegrating Russia into the world economy and the costs associated with normalizing relations with Ukraine and the West.

The economic shock of an end to the war over the near to medium term will not be as serious as the one that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. But it still will be extremely painful.

.jpg)